Go Get That Sticker!

How voting in America actually works and what this means for 18-year-olds

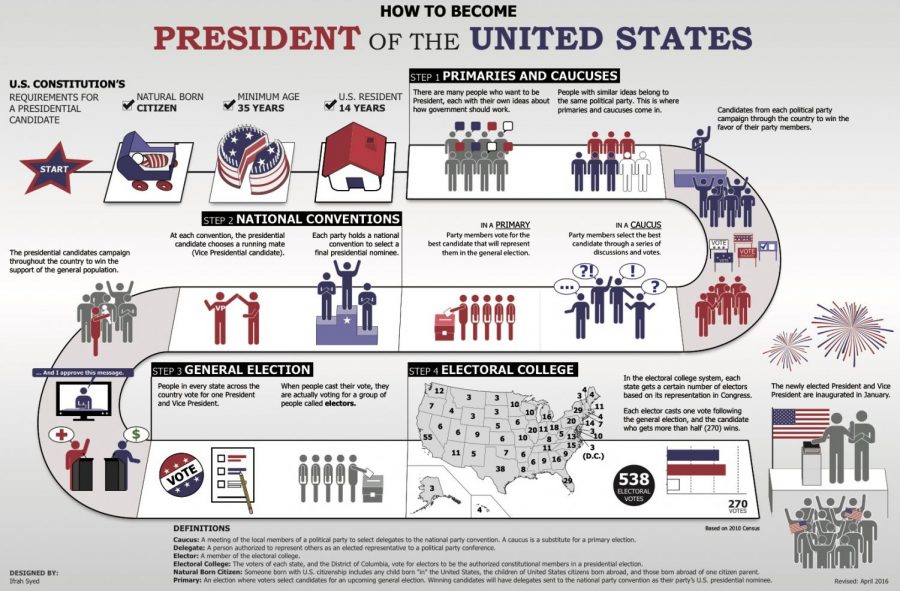

The process to become the President of the United States.

Every four years in November, the country is filled with anticipation, tension, and uncertainty as Americans anxiously wait to see who will win the presidency, who will be chosen to lead our country for the next term, who will institute his or her agenda in the coming years, potentially causing major changes in our nation.

I would venture to guess that most Americans strongly value their right to vote and hold it dear, yet compared to other highly developed countries, the U.S. voter turnout is actually quite low. According to a 2018 study from Pew Research Center, “Nearly 56% of the U.S. voting-age population cast ballots in the 2016 presidential election, representing a slight uptick compared with 2012 but less than in the record year of 2008. While most Americans – 70% in a recent Pew Research Center survey – say high turnout in presidential elections is very important, what constitutes ‘high turnout’ depends very much on which country you’re looking at and which measuring stick you use.”

It would seem that because voting is a key pillar of the foundation of the United States, a lasting symbol manifesting how our founders valued freedom, democracy, and the power of the people, that more Americans would take advantage of this opportunity to vote, especially now that we have finally achieved equality among citizens with regards to voting. According to USAGov, “the 15th Amendment gave African American men the right to vote in 1870,” “the 19th Amendment, ratified in 1920, gave American women the right to vote,” and many acts have been passed to ensure voting is actually accessible and practical for these citizens.

Pew Research Center lays out the statistics from the most recent presidential election, one that Time called “one of the most shocking U.S. elections in modern political history” because it marked the fifth time in history that a president won the Electoral College (and therefore, the White House) while losing the popular vote: “The Census Bureau estimated that there were 245.5 million Americans ages 18 and older in November 2016, about 157.6 million of whom reported being registered to vote. . . Just over 137.5 million people told the census they voted in 2016, somewhat higher than the actual number of votes tallied – nearly 136.8 million, according to figures compiled by the Office of the Clerk of the U.S. House of Representatives, though that figure includes more than 170,000 blank, spoiled or otherwise null ballots.”

Although voting is not required or mandatory by any means (according to USAGov, “In the U.S., no one is required by law to vote in any local, state, or presidential election. According to the U.S. Constitution, voting is a right and a privilege.”), the focus around politics as well as the controversy and division that arise from almost every mention of the president or the upcoming election (and of course, past elections) suggest that Americans are passionate about this topic — and that perhaps, more should take advantage of their vote.

The voting process and the road to the White House are unique to the United States, and they explain why it is possible for a candidate to lose the popular vote yet win the presidency. Let’s take a quick look at the presidential election process — and who Americans will actually be voting for on Nov. 3, 2020 (hint: it’s not actually the president!).

Beginning with primary elections and caucuses, which are essentially “local gatherings of voters” (USAGov), potential presidential nominees are found and voted on; these are currently happening for the 2020 election. Following these, the nominating conventions take place, “during which political parties each select a nominee to unite behind. During a political party convention, each presidential nominee also announces a vice presidential running mate” (USAGov). Around late summer/early fall, these candidates will then campaign across the nation with the goal of gaining support and popularity as they explain their views, agendas, and intentions to voters. Debates with opposing candidates are also a distinct aspect of the election process, giving candidates an opportunity to portray their contrasting views on television, in front of the whole nation.

Then on the first Tuesday following the first Monday in Nov., voters cast their ballots for president, but this vote does not actually determine the president, meaning that technically Americans do not vote directly for the presidency. In 48 of the states as well as Washington, D.C., the winner of the popular vote is awarded all of the electoral votes for that state, meaning that the electors for that political party will be given the electoral votes. According to USAGov, “Each state gets as many electors as it has members of Congress (House and Senate). Including Washington, D.C.’s three electors, there are currently 538 electors in all. . . Each state’s political parties choose their own slate of potential electors.”

In order to win the White House, a candidate must receive at least 270 electoral votes (more than half of all the electors’ votes). Generally, a winner is announced on Election Day in Nov., “but the actual Electoral College vote takes place in mid-December when the electors meet in their states. The Constitution doesn’t require electors to follow their state’s popular vote, but it’s rare for one not to” (USAGov). What this means is that it’s actually possible to have a “faithless elector,” who chooses to vote for the opposing party’s candidate, which could potentially alter the results found on Election Day. Although there have been 167 faithless electors in U.S. history, they have very rarely made an impact on the final decision.

Jeff Gall, Ph.D, history department chair and upper school history teacher, offered his thoughts on the American voting process: “I think our system works well and is a model for the world. Anyone with a minimum amount of effort can register and vote. As for knowing who they are voting for, I think all of us SHOULD wait to examine the candidates through the entire election season, but unfortunately, most Americans are locked in their silos and have likely already decided who they support.”

So, now that you’ve had a brief refresher on how our complex system works, do you plan on voting in the upcoming election? For many Westminster seniors, voting is finally becoming a reality, and the 2020 election will be the first election we are able to vote in — most of us as 18-year-olds just entering college.

For many of our siblings or friends who are several years older, some of whom will be over 21 years old at the time of the election, this is also their first opportunity to vote. The class of 2020 happens to have a unique chance to vote this year, just a few months after becoming adults. 18 years old may seem to be relatively young to make such an important decision, but as adults who are now (almost) independent and are gaining more freedom and autonomy everyday, I believe this is a welcomed opportunity, a chance for 18-year-olds to experience a taste of adult life and develop a greater appreciation for our country.

“I do think [the voting age of 18] is appropriate. If one is old enough to join the military and put his/her life on the line – that person is old enough to vote for the politicians who will send young people to war. Some teens do think critically about the issues and vote with their eyes wide open, others I work with seem very unprepared. But I don’t think that is so much different for many older Americans,” explained Dr. Gall.

Dr. Gall introduces an interesting perspective — it’s possible that age is not necessarily the issue. Perhaps what America needs more of is actually curious, well-informed Americans who truly desire to understand the process and to focus more on finding the best leader for our country, rather than destroying the opposing candidate and his/her supporters.

“I think one of the most troubling aspects of today’s political landscape is how woefully uninformed most voters are. Many people don’t bother to be informed at all, and many others limit themselves to news from one perspective. They watch FOX or they watch CNN. We owe it to ourselves to watch and read news from all over the political spectrum. That is how we can truly assess key issues,” said Dr. Gall.

I believe it’s possible that 18-year-olds may actually be more inclined to inform themselves and take their participation in the upcoming election seriously. We’ve all freshly studied government and the election process, and we understand the value of our right to vote. This is new and exciting — a step into the real world — and most of us don’t want to squander this opportunity.

“I truly believe that voting remains the most important civic duty. As 18 year-olds, I think it is especially critical to be an informed voter. If we have this right, we need to use it appropriately. Whether reading newspaper articles, watching debates, or listening to the news, try to find the truth behind each candidate and look for genuine people who you believe would be great leaders of our country,” said Lea Despotis, senior.

Dr. Gall offered his own especially memorable first voting experience: “I was actually the first 18-year-old in U.S. History to vote in a presidential election — in 1972. Well, I was TIED with several million other 18-year-olds that year, but it WAS the first presidential election after the 26th Amendment became law, letting 18-year-olds vote. I just happened to be 18 that year. I was VERY excited and remember filling out that ballot quite well. But no way I am telling you who I voted for (Nixon or McGovern)!”

So, to all of the seniors graduating this year, take advantage of this chance to discover what you believe and who and what you plan to support.

Dr. Gall gave some words of wisdom to new voters: “Ben Franklin famously said we ‘have a republic, if we can keep it.’ We are always in danger of losing it if we do not exercise our responsibilities as citizens. Get informed and vote. If you run out of time, just come see me, and I will tell you who to vote for :-).”