Practicing Confident Pluralism

As partisan politics witnesses rising hostility, young citizens should seek a new direction.

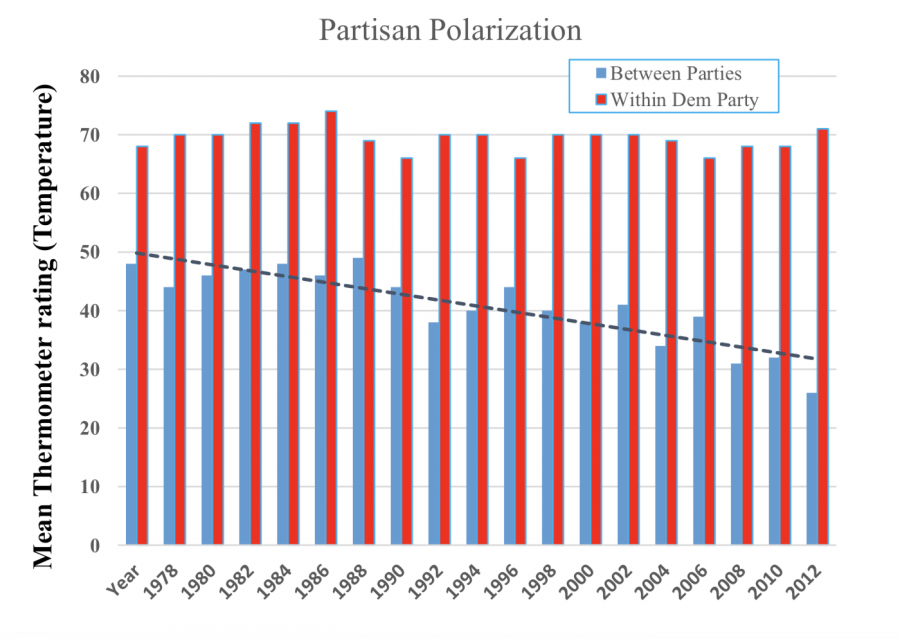

Affective partisan polarization. Americans’ feelings toward their own party have barely changed since the 1970s, but Americans have become more “cold” toward the other party since the 1990s. (Source: American Election Study)

On Sep. 24, 2017, many of the Pittsburgh Steelers kneeled during the national anthem after President Trump openly expressed his opinion that players should remain standing. The Steelers coach Mike Tomlin responded, “We’re not going to play politics.” The reality of that statement, however, is simply impossible: everything is political.

Over the last two years, companies such as Nike, Chick-fil-A, Hobby Lobby, Nordstrom, and Starbucks have all been targets of political boycotts related to contentious political and social issues. In response to corporate political activity, public calls to patronize certain retail establishments have dramatically increased. Mainstream and cable news networks, Hollywood award ceremonies, television programs, and sitcoms all add biased political spin to influence and promote social agendas.

Politics is—and always has been—invading everyday life; the restaurants you support, the places where you worship, the stores you shop at, and the media you follow can all imply a political statement.

But in the last few decades, a sharp divide in political identity amplifies the brewing “us vs. them” mentality sweeping across the nation. With the rise of social media platforms like Twitter and Facebook, information penetrates rapidly and expansively, perpetuating a rising animosity in our polarized politics. The United States is mired in a partisan hyper-conflict that is dividing politicians, communities, and even families. As our nation faces seemingly irresolvable disagreements, many wonder: Can we just get along?

Dr. John Inazu, a Sally D. Danforth Distinguished Professor of Law, Religion, and Political Science at Washington University in St. Louis, suggests that there is a way.

In his book Confident Pluralism, Inazu provides realistic guidelines that encourage peaceful cohabitation in society despite ingrained differences. The United States was founded upon the fundamental philosophy of pluralism, as partisan politics differentiates how people view the purpose of country, the meaning of common good, and the definition of human thriving. However, the very principles that so divide us also distinguish us. While maintaining our diverging practices and beliefs, Confident Pluralism argues that Americans can elevate the conversation through civic aspirations that value tolerance, humility, and patience over protest, defensiveness, and coercion.

“We need to find the best civil and legal way to preserve difference, but then allow dialogue across difference,” says Inazu, “We can begin by looking for common ground. We can form some sort of bond that then allows us to build upon our relationship with trust.”

To forge a new path forward, society shares the collective responsibility to embrace the civil practices of confident pluralism. As the young minds of America shape the future, it’s necessary that students today acquire the skills to change the dysfunctional trajectory in an increasingly polarized political climate. After an enlightening interview with Dr. Inazu, I have learned identifiable ways that we, at Westminster Christian Academy, can inspire progress.

“Everyday that goes by we are more worried about social media as our primary mode of communication with each other, so a practical step for current students is to figure out if there are ways to prioritize face-to-face relationships and communication,” says Inazu, “As students move on to college, think about how you can be deliberate about diversifying your inputs and newsfeeds, so that you can be exposed to different viewpoints and ideas about our national politics.”

In a technologically connected world, the mask of anonymity inherent in faceless online interactions fosters greater incivility. To avoid the corrosive hostility, Inazu recommends a cautious approach to disseminating political commentary via the internet.

“One thing to practice now is to set up the kind of habits that you are going to need for college and beyond. I think one of those is to step out of the sense you need to respond immediately to the world. When you hear about something that you don’t like, wait hours before you post something online. Once it’s out there it’s out there. Realize the world is a big place and we are limited in our ability to know. Find a way to speak confidently about the things you know about and don’t be overconfident about the things you don’t know,” says Inazu.

Additionally, in a more sheltered environment such as a Christian school, students must also realize the importance of developing a diversified community to navigate through impending political and social tensions.

“There are a lot of places and institutions we will find ourselves in that have their own blind spots. First, recognize where you are and the upsides and downsides of being at this space and how to protect against being part of an echo-chamber. It is important to not be influenced by all the same voices and be sure to allow for self-reflection,” says Inazu.

“Our challenge is, whatever the constraints are, maximize the ability for confident pluralism within those constraints. Be really willing to push each other on difference and don’t assume consensus within those constraints.”

As politics infiltrates our lives, the tenor of the times reveals that we must demand more of our citizens and halt the crippling political rancor. As we prepare for the onslaught of negativity undoubtedly expected in the 2020 election, future voters must strive towards exercising civil practices that enhance productive political discourse. If we’re going to continue to “play politics,” let us proceed confidently in our pluralism.